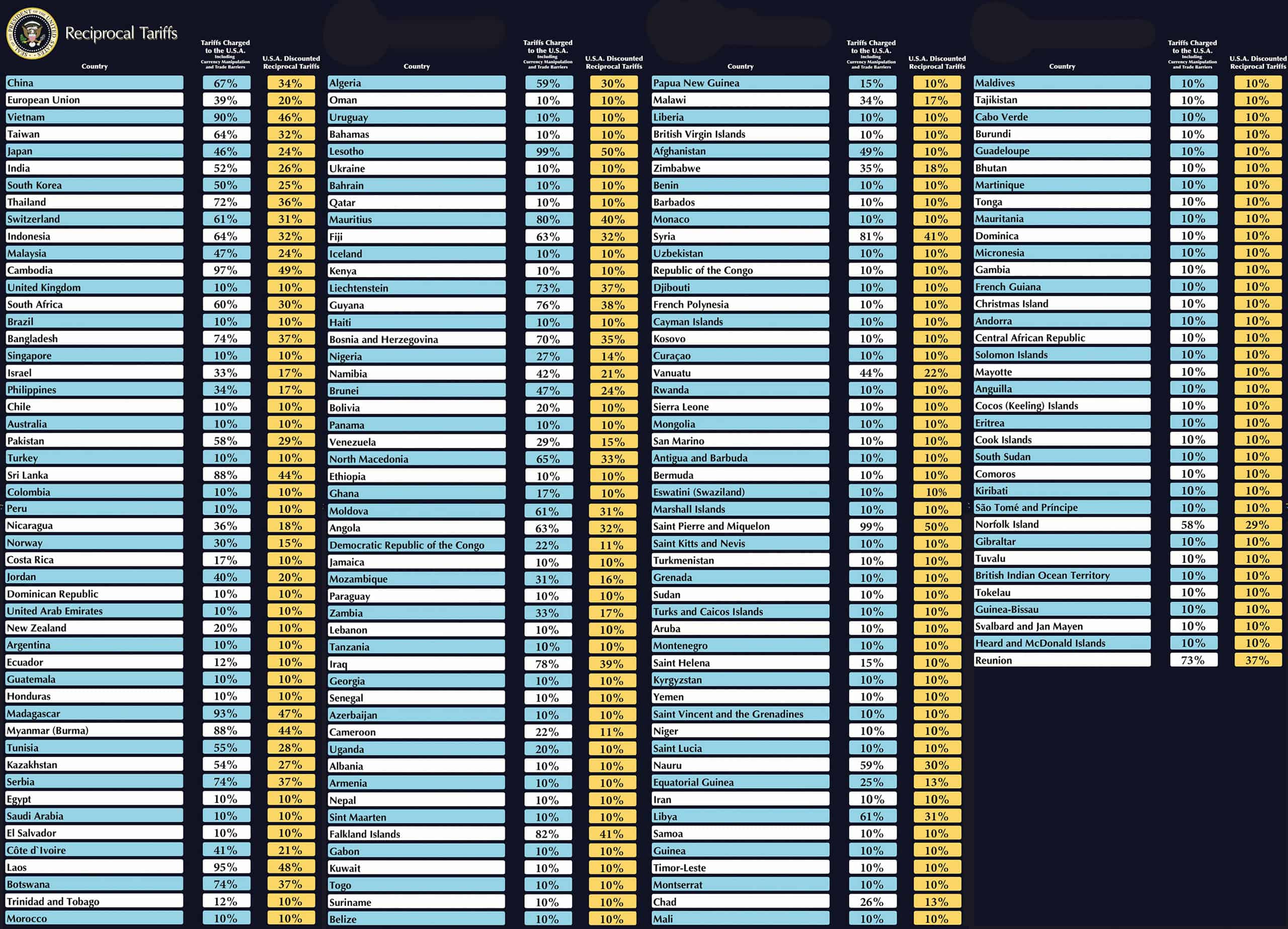

Reciprocal Tariffs

In February the White House announced sweeping plans for broad-based reciprocal tariffs against any country that has trade barriers in place against U.S. goods.

The memorandum read in part: “It is the policy of the United States to reduce our large and persistent annual trade deficit in goods and to address other unfair and unbalanced aspects of our trade with foreign trading partners. In pursuit of this policy, I will introduce the ‘Fair and Reciprocal Plan’ (Plan). Under the Plan, my Administration will work strenuously to counter non-reciprocal trading arrangements with trading partners by determining the equivalent of a reciprocal tariff with respect to each foreign trading partner.”1

Initially, this was a response to foreign tariff rates set against the U.S. For instance, the U.S. would charge Indian goods the same tariff that India charges for American goods. However, the tariff calculation appears to be based on the trade imbalance. The method involves subtracting U.S. exports from imports (the trade deficit), dividing that figure by the total U.S. imports from the country in question, and then halving the result.

Using Angola as an example: U.S. exports to Angola total approximately $700 million ($0.7 billion) annually, while imports from Angola amount to $1.9 billion, creating a trade deficit of about $1.2 billion. Dividing 1.2 by 1.9 is approximately 63%, which corresponds to the “Tariffs Charged to the U.S.A.” chart presented during the February policy announcement. Halving this percentage produces the tariff rate applied to goods from Angola.

However, this figure does not reflect Angola’s actual tariffs on U.S. goods, which average around 7.3%. Angola is being penalized with higher tariffs primarily because of the trade imbalance — driven largely by U.S. imports of oil — rather than high trade barriers against American goods. If the objective is to make U.S. goods more competitive for American consumers, this approach may still serve that purpose, but it does not align with the original principle of reciprocal tariffs.

Analysis from the Budget Lab at Yale University shows that the U.S. is now at its highest effective U.S. tariff rate since 1901.2 The resulting upward price pressure could lead to an increase in inflation of 3 percentage points (currently at 2.8%; it could jump up to 5.8% in the short run). Assuming spending mirrors 2024 patterns, that would lead to a decline in the average real disposable income per household by about $4,900 in 2025.3 Overall, this would be felt as a decrease in GDP and employment levels and heightened recession risk for the economy.

In April, the White House announced a temporary, 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs but in recent days that timeline has been less certain.