An Economy in Contrast: Strong Output and Slowing Job Market

The first half of the year has been puzzling for economic observers: resilient consumer spending and economic growth despite a rapidly weakening labor market1. To understand this strange dynamic, we must first look at the wild swings in our Gross Domestic Product (GDP) data and then figure out how Americans are managing to keep spending up when hiring is slowing down.

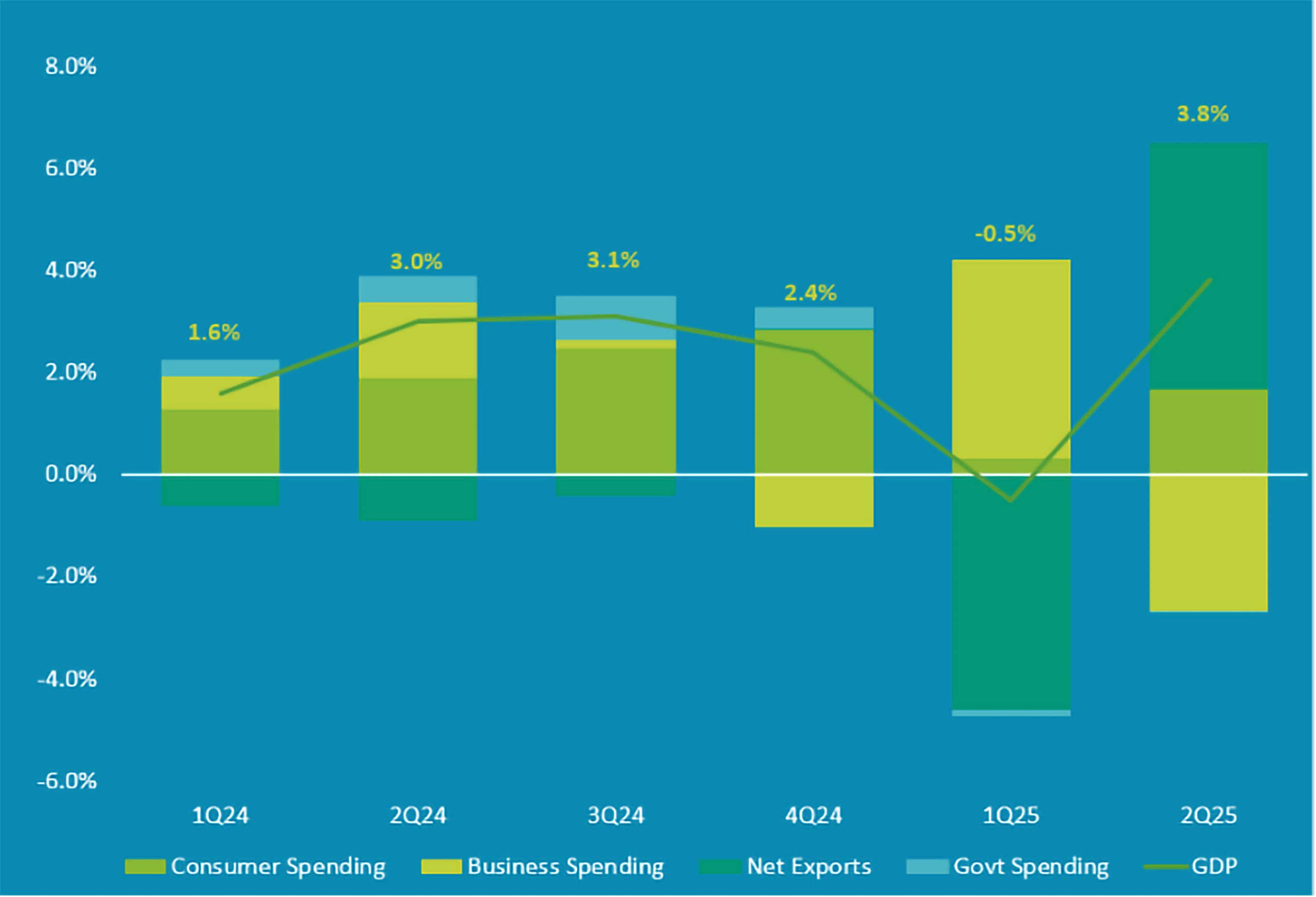

Drilling down to the core components of GDP — consumer spending, business investment, government spending, and net exports (exports minus imports) — is where we see what makes the first half of 2025 so unusual.

Source: JE Dunn Construction, Bureau of Economic Analysis

In the first quarter, we saw the first negative GDP reading in three years. This was largely driven by a massive, negative reading on net exports. The sudden drop was a direct consequence of businesses rushing to get ahead of impending trade policy changes. Companies imported far more than usual, not just consumer goods for store shelves, but also intermediate goods like semiconductors, car parts, and building materials used in domestic production. This surge of imports, which outpaced our exports, pulled the GDP figure down. The silver lining for this behavior change is that, by taking on these tariff-related costs upfront, businesses temporarily shielded consumers from immediate, sharp price increases.

The second quarter saw the pendulum swing back in the other direction. With so many imports already brought in during Q1, the need for further purchasing dropped significantly — these were purchases that would have been made over the course of the next few months, but instead they were moved up to Q1 and thus didn’t need to be made in Q2. This translated to Q2 net exports skewing highly positive, with a very small number of imports subtracted, giving a massive boost to GDP.

Consumers also in the second quarter than in the first. The latest revisions to Q2 GDP shifted growth from 3.3% to 3.8%, fueled mostly by upwardly revised consumer spending numbers. Even when you smooth out the trade volatility by looking at the first half of 2025, we still managed 1.1% positive growth — not stellar, but still expansionary.

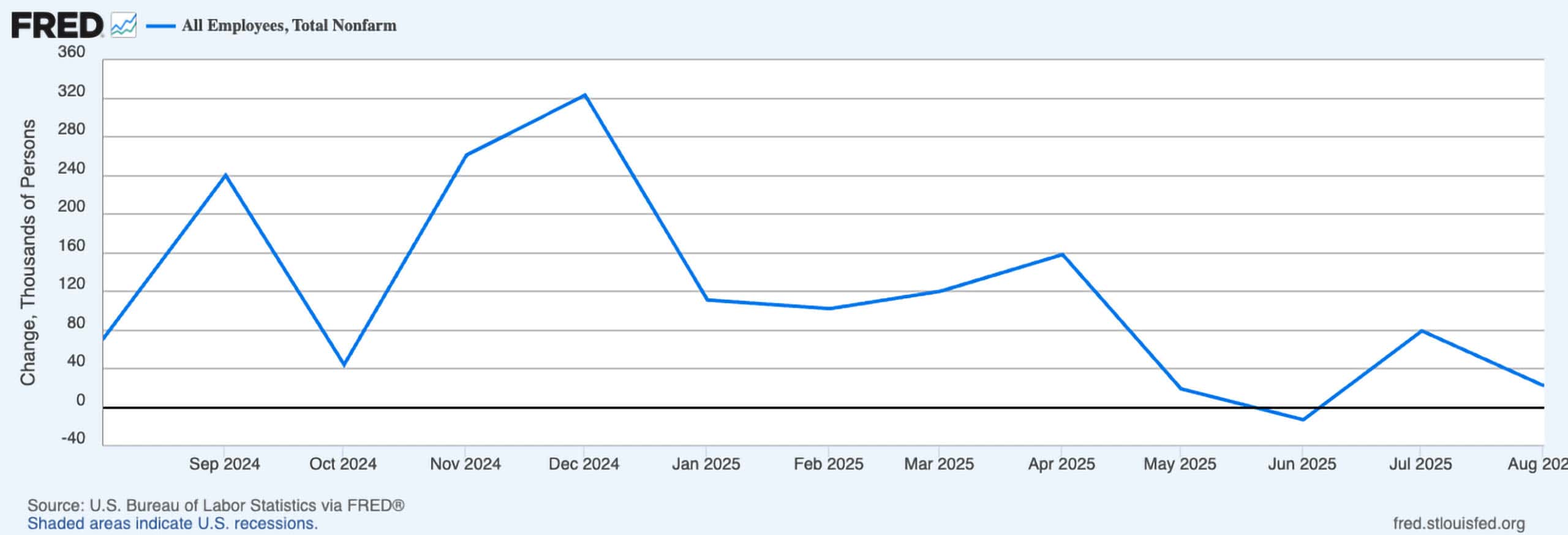

Amidst this GDP growth, the labor market appears to be weakening significantly. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the number of jobs added has declined in five of the last eight months. Since May, the average monthly jobs gain has plummeted, falling to roughly 27,000 jobs added per month — low enough to force the Federal Reserve (Fed) to shift its focus from tamping down inflation to bolstering employment.

That leaves us with something of a puzzle: modest GDP and a resilient consumer coexisting with a collapsing job-growth figure. How do we reconcile these conflicting data points? Two primary factors are at work: demand and supply changes in the labor market and a shifting consumer spending demographic.

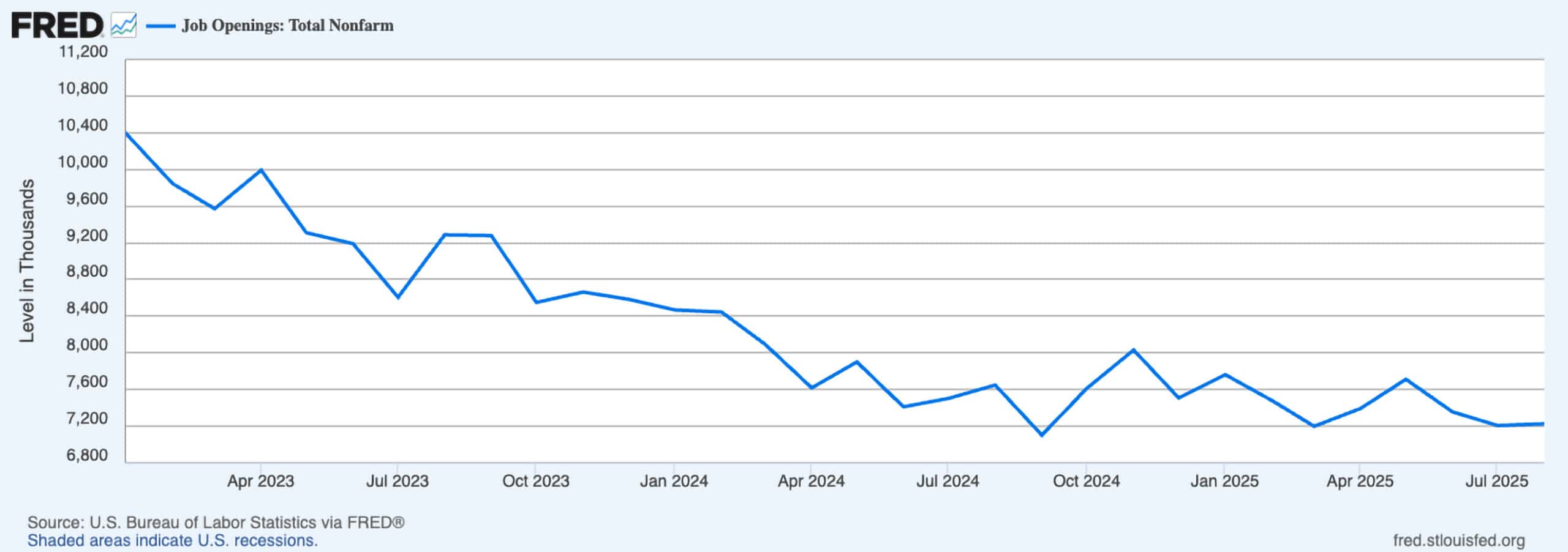

The first thing that can be gleaned from the data is that labor demand is weakening. That can be seen not just in the lower number of jobs added but also in the number of job openings. The Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) data shows us that the number of openings is in decline. This is not as big of a decline as what is seen in the jobs added figures, but it is still large enough to show that businesses are being cautious — a reaction to uncertain trade policy, and perhaps the implementation of AI to some degree.

Businesses are also hiring fewer people because there are simply fewer people to hire. The labor force has seen an average monthly loss of about 90,000 people since May. The biggest driver behind this supply shock is likely stemming from lower immigration levels. The consumer make-up has also shifted. While most Americans rely on the labor market for their spending power, the wealthiest are less impacted by a slowing labor market when compared to most of the labor force. The highest-earning 10% of consumers now account for around half of all consumer spending2. This segment of the population is largely keeping the GDP engine moving forward despite the overall decline in the labor market and its impact on the bottom 90% of earners. The reliance on top earners is not a sustainable formula for long-term expansion. We are likely approaching a turning point. We’re soon going to see either a) a substantive decrease in GDP as the half of consumer spending supported by the bottom 90% of consumers slackens more than what the wealthiest can make up or b) the labor market strengthens as we move past the worst of the current elevated uncertainty levels and businesses gain more confidence in future growth, the labor participation rate potentially increases enough to compensate for lower immigration, and lower-income consumers see more resulting wage growth.

The Fed recently resumed cuts to the Federal Funds rate with a 25-basis point cut at the September Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, bringing the upper limit from 4.5% down to 4.25%. The Federal Funds rate is the rate at which banks can lend their reserve balance to other banks overnight so that the borrowing bank can cover its reserve requirements. This works out then, to be the cost of money for banks, and that, along with the need for the spread required to make a profit, influences the price that they charge to loan their money out to other, non-bank customers. The more direct impact of Federal Fund rate cuts is on short-term lending. We don’t see the same kind of movement in long-term rates, as they are more heavily influenced by market forces like supply and demand. But the underlying influence from the Federal Funds rate remains. The 25-basis point cut was widely anticipated and has likely already been priced into the market. It’s a pretty small cut, however, and we don’t anticipate a lot of change in demand for construction loans as a direct result of the cut, because we are still in restrictive territory due to monetary policy. At the margin, we expect modest gains in lending and spending. Lower rates on things like credit cards will free up some disposable funds for the consumer. What is likely to be a bigger factor is the mood shift that can occur as we enter into an easing cycle. This cut, the first since last December, is a signal that the Fed is willing to focus on growth again, and this is the path to that growth.

Fed chair Jerome Powell recently noted: “A reasonable base case is that the effects will be relatively short-lived — a one-time shift in the price level. Of course, ‘one-time’ does not mean ‘all at once.’ It will continue to take time for tariff increases to work their way through supply chains and distribution networks. Moreover, tariff rates continue to evolve, potentially prolonging the adjustment process”3.

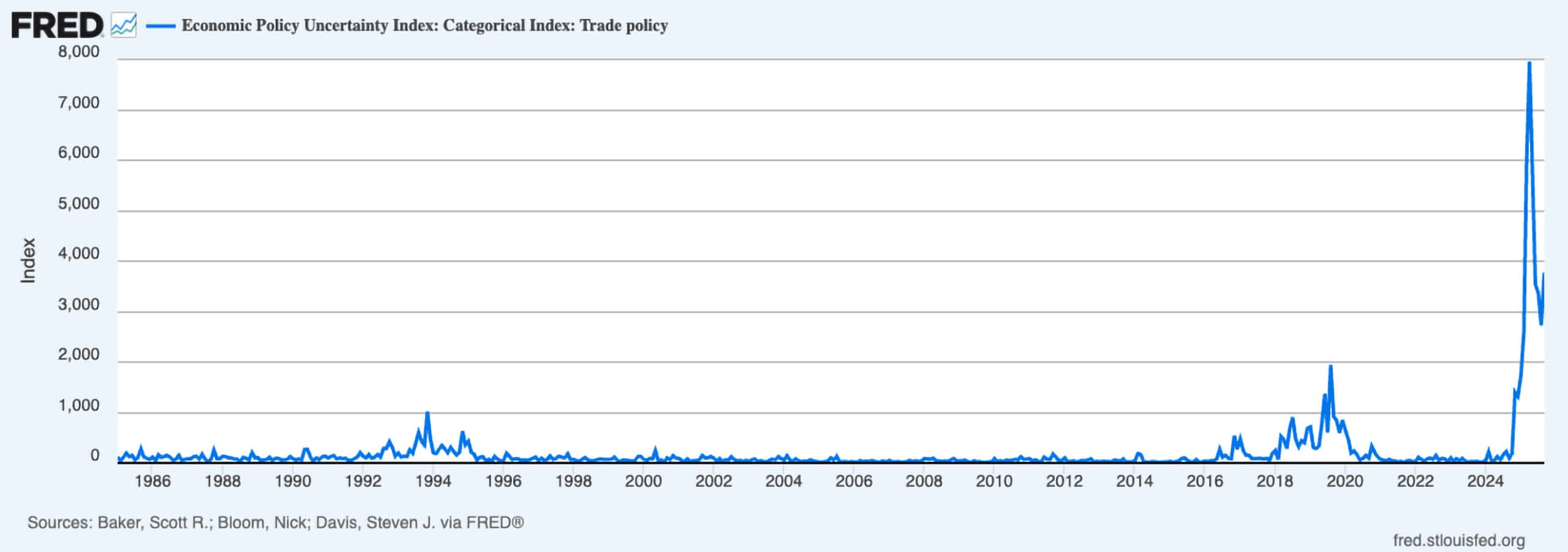

While it is true that the price shift is taking a while to get through, and we think that more inflation is yet to come, now that the dust is finally beginning to settle on trade policy changes, it’s reasonable to think that the external upward price pressure is going to come to an end soon. This dynamic will have an even larger impact on the economy at large than the rate cut. While still extraordinarily high, trade policy uncertainty and general economic uncertainty, as measured by , are both coming back down to earth again as fewer major policy shifts are made4.

Perhaps the most valuable gift of the Fed’s rate cut is a modest reduction in the fog of economic uncertainty. For the better part of the last two years, the construction industry, along with the economy as a whole, has operated with a “wait-and-see” mentality, driven by high inflation, volatile interest rates, and geopolitical instability. This uncertainty has been a major inhibitor of long-term investment and project planning.

The Fed’s decision signals a belief that the soft landing for the economy is still achievable — that inflation can be tamed, or at this point, outlasted, without triggering a severe recession and we can still generate positive economic growth, as measured by real GDP. This confidence signaling can help unlock delayed and sidelined capital investments and give developers and businesses more of the clarity they need to move forward with new builds and expansions. The impact is not instantaneous, as project timelines are long, but the sentiment shift will start to become clearer.

Forecast

Our outlook for 2025 into 2026 is that the two things that we’ve been waiting on — a more stabilized trade policy and the resuming of the Fed’s rate cutting cycle— will help the economy move more firmly back into expansion with real GDP showing modest growth and the labor market recovering as businesses feel confident enough about the future to begin hiring again.

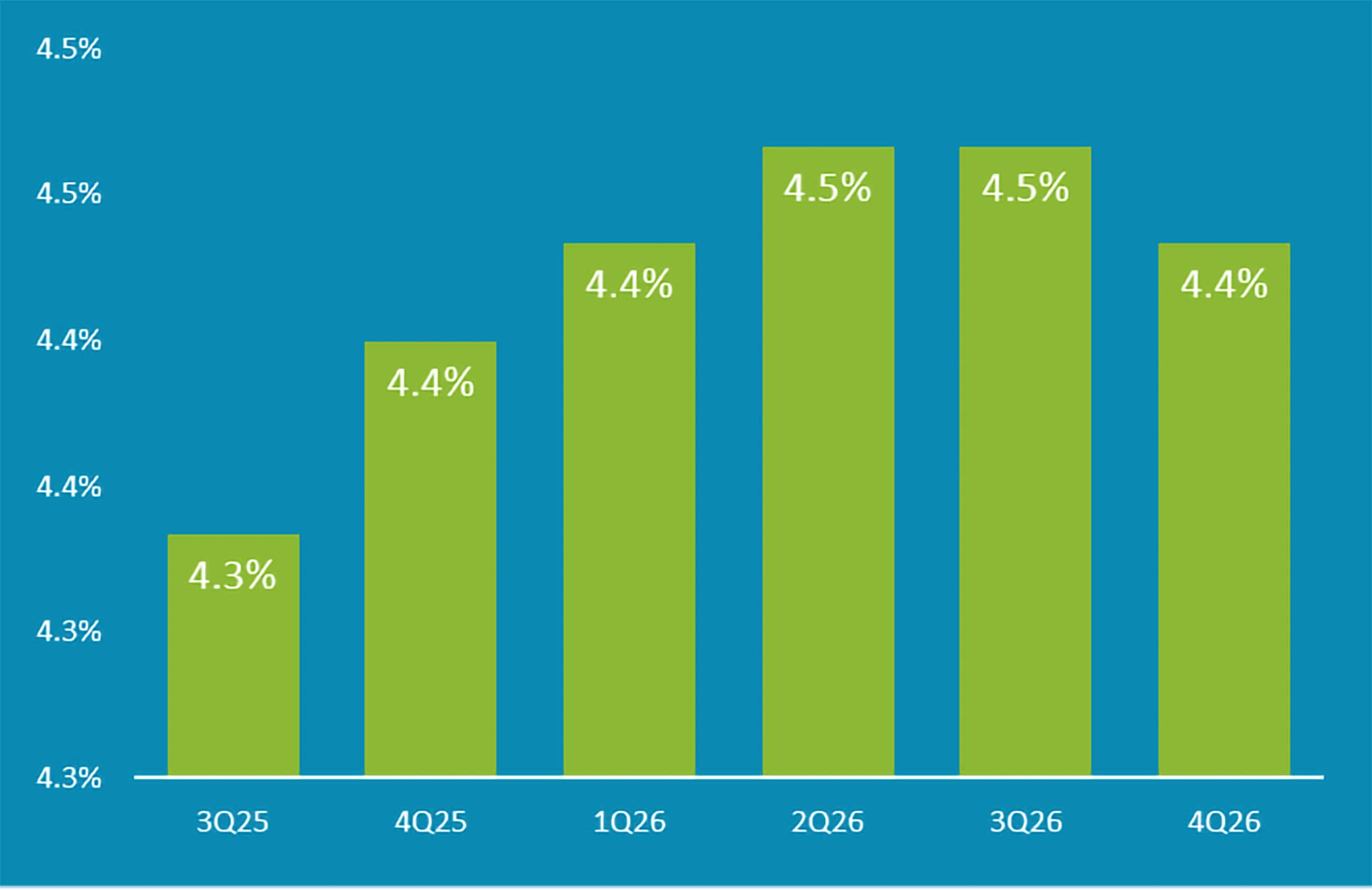

GDP FORECAST GRAPH

Real GDP recovers as we move into 2026 as this is an economy that still has some gas in the tank. The main impediment has been external (see uncertainty, tariffs) as that clears, we see spending strengthen and demand levels expand across sectors.

Source: JE Dunn Construction, Bureau of Economic Analysis, Oxford Economics

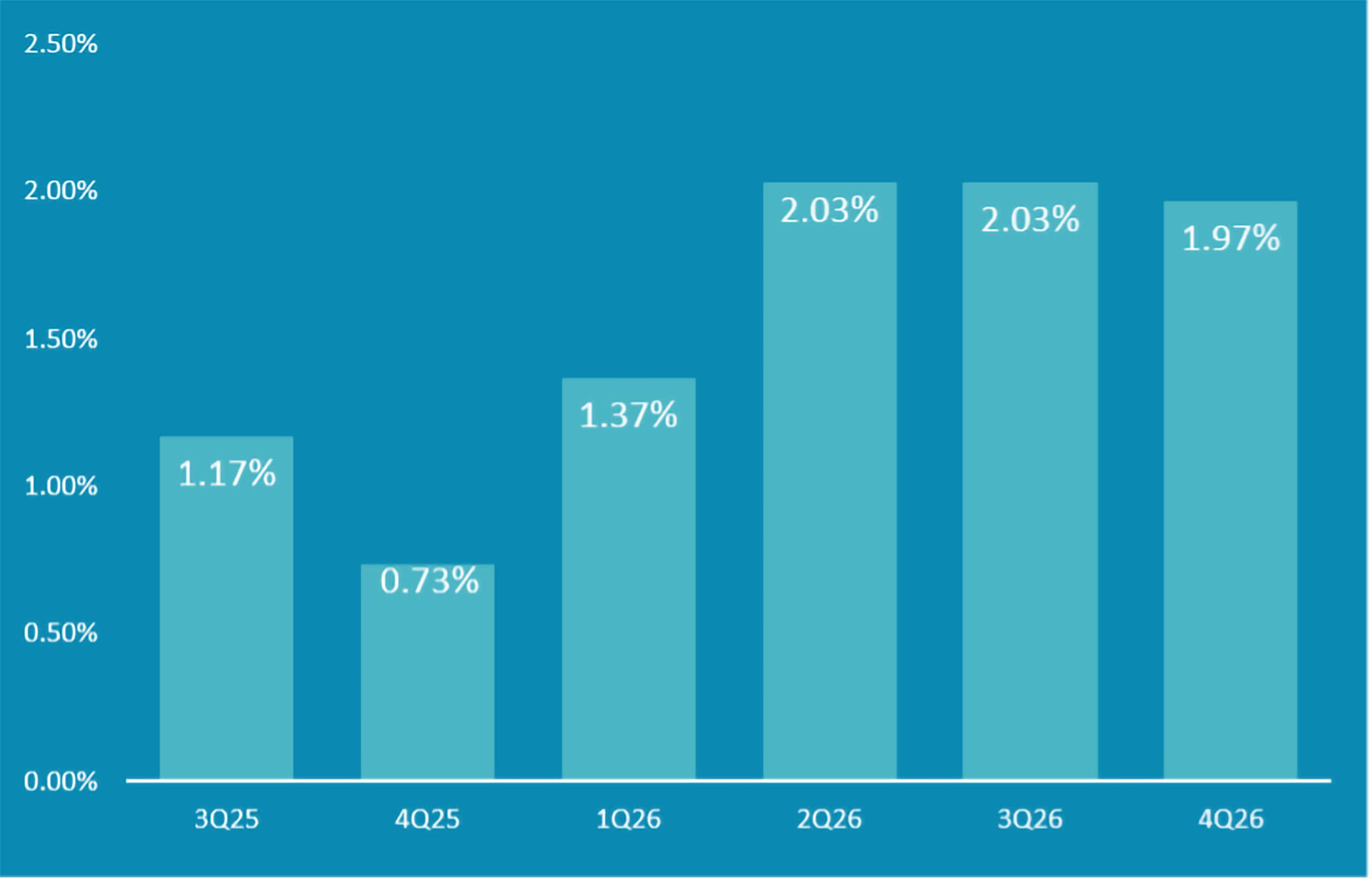

UNEMPLOYMENT RATE FORECAST GRAPH

The labor market is slower to respond as it typically operates on a lag (it takes time for businesses to be convinced that demand is there to support more hiring and then it takes time to do the actual hiring) so we see the unemployment rate getting worse before it gets better but it still benefits from these same forces, lower uncertainty and three rate cuts, and we anticipate that it will start falling again by the end of 2026.

Source: JE Dunn Construction, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Oxford Economics

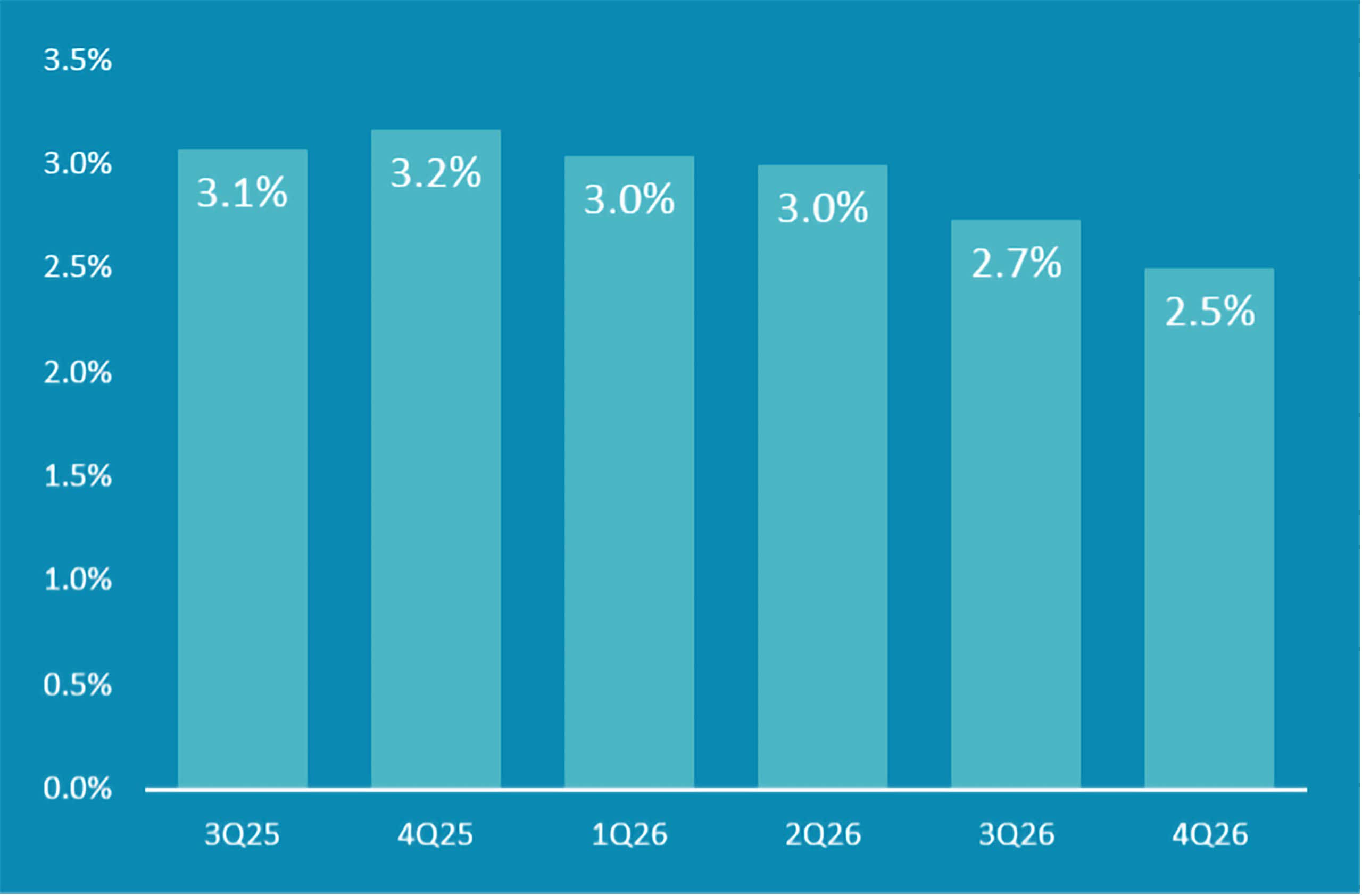

INFLATION FORECAST GRAPH

Inflation increases to over 3% as we crest the full wave of tariff-induced inflation. Once we are past that there will still be some additionally upward price pressure as growth regains its footing but we are still close to neutral rate territory, so inflation is better behaved in 2026.

Source: JE Dunn Construction, Bureau of Economic Analysis, Oxford Economics

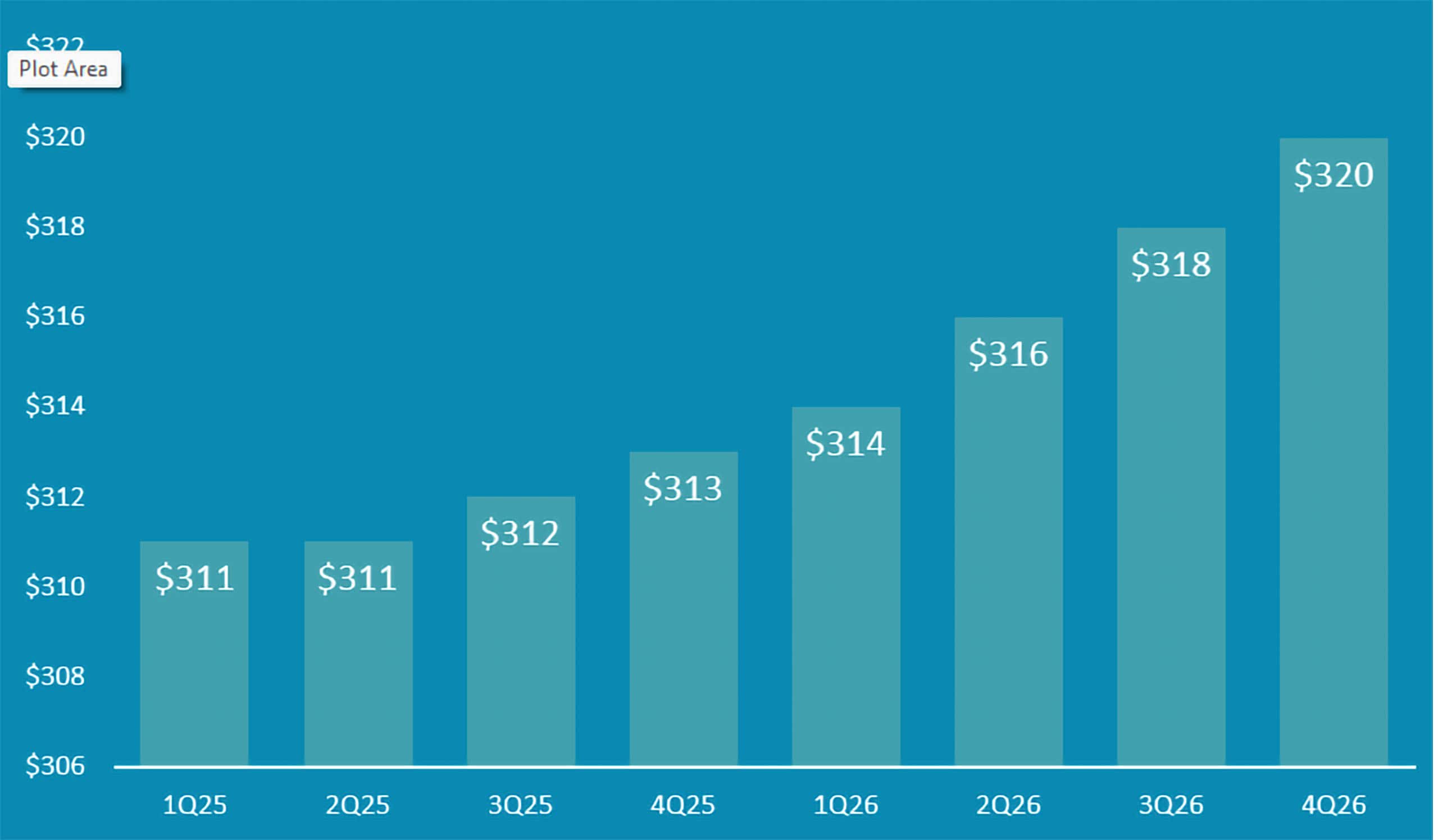

NON-RESIDENTIAL CONSTRUCTION SPENDING FORECAST GRAPH

The construction market benefits from these forces as well and we return to nominal year-over-year growth by the middle of 2026. Those figures include inflation— when we look at non-residential spending in real terms, we will be flatter in 2026 but moving in the right direction again as it turns towards growth.

Source: JE Dunn Construction, Census Bureau, Oxford Economics

Sources

- Bureau of Labor Statistics: https://www.bls.gov/bls/newsrels.htm#OEUS

- https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/19/business/economic-divide-spending-inflation-jobs.html

- https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20250822a.htm

- https://www.policyuncertainty.com/